Last night as I watched The Green Mile with my husband, I was reminded of a particularly moving visit we had taken to the Abbey of Clairvaux in July.

What could a 12th century abbey and The Green Mile have in common? You’re about to find out.

Expectation VS Reality

To be honest, I had a presumption of what the abbey would be like given my art historical background and previous travels, but I must admit, I had not done any research into its later history or condition past Bernard’s occupancy.

You can imagine how confused I was when I went to look it up on google maps, finding the entire zone was pixilated. Obviously, this made me pose some questions, and I soon had a response: the “Maison Centrale de Clairvaux” (Clairvaux Prison) is on the site of the abbey – SURPRISE!

After finding that out, I was a bit hesitant and nervous to go, but I am glad that I went because the visit was extremely touching and gave great insight into several important parts of French history.

The History of the Abbey of Clara Vallis (Clear Valley)

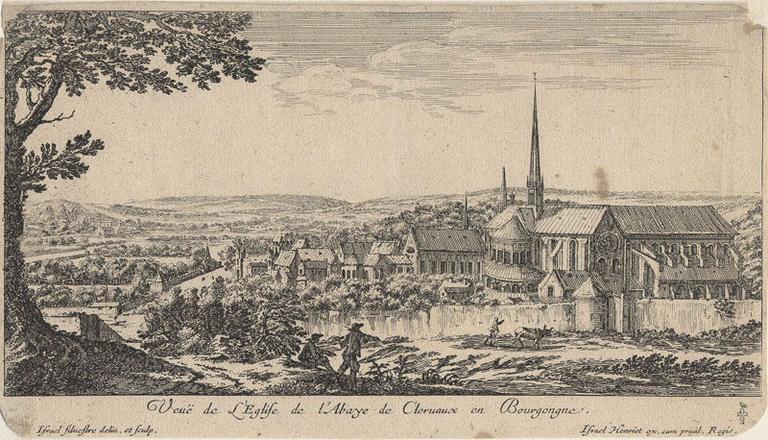

Established by monks coming from the Abbey of Cîteaux in 1115 lead by the would-be Saint Bernard, the Abbey of Clairvaux is one of the first abbeys founded as “daughter monasteries” of the monastery of Cîteaux, itself founded in 1098 by Abbot Robert de Molesmes and his followers. Molesmes was a Benedictine monk who desired to practice the Rule of Saint-Benoît (Saint Benedict) with more fidelity and stringency, thus creating the abbey of Cîteaux (Cistercium in Latin) and, therefore, the Order of Cistercians.

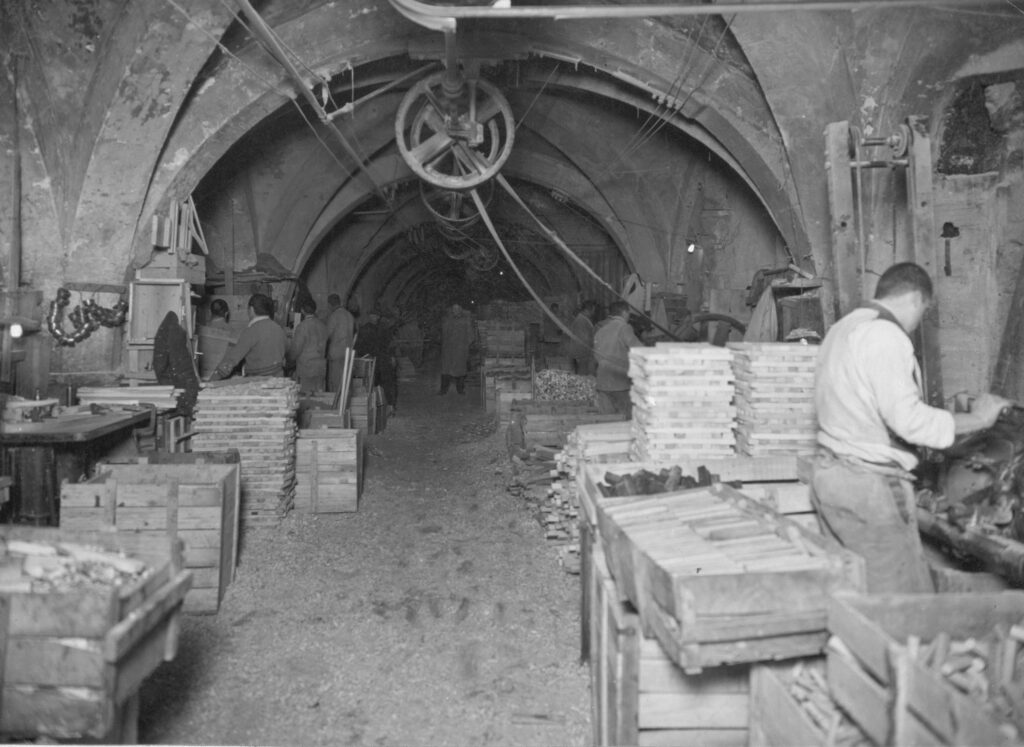

The abbey was the home of two types of religious men: the “moines de choeur” (choral monks) and the “frères convers” (lay brothers). The lay brothers were charged with working on, and developing, the abbey estates: vineyards, farmland, salt mines, metalworks and forestry. While the lay brothers brought prosperity to the abbey, the monks devoted their time to studying scripture, praying and working in the “scriptorium” where they copied the holy books as well as great works of Greek and Latin literature. By the time of the French Revolution, the abbey library held over 40,000 works.

Left: Illuminated manuscript depicting Bernard, dated 1267-76

The 12th Century Abbey

The abbey and its grounds have gone through several changes throughout time, and none of the structures from the first abbey survive.

Around 1135, the site of the abbey moved east. Unfortunately, the building program was not finished before Bernard’s death in 1153; it would take another twenty-one years for the abbey church to be dedicated and Bernard himself canonized (i.e. become a saint). The only remaining structure of this time period is the “bâtiment de convers” (building of the laypeople) which housed a dormitory in the upper level and a refectory and storeroom in the lower.

The 18th Century Abbey

By the 18th century, the abbey had 40 monks and 20 lay brothers and was in great financial standing. After nearly 600 years, the monks were able to commission an (almost) entirely new complex of buildings. The rebuilding began with the “grand cloître” (great cloister) in 1767 that afforded each monk his own individual (but modest) room, while at the same time, the 16th century mill and oven building was also reconstructed to create “architectural harmony” with the new Baroque cloister.

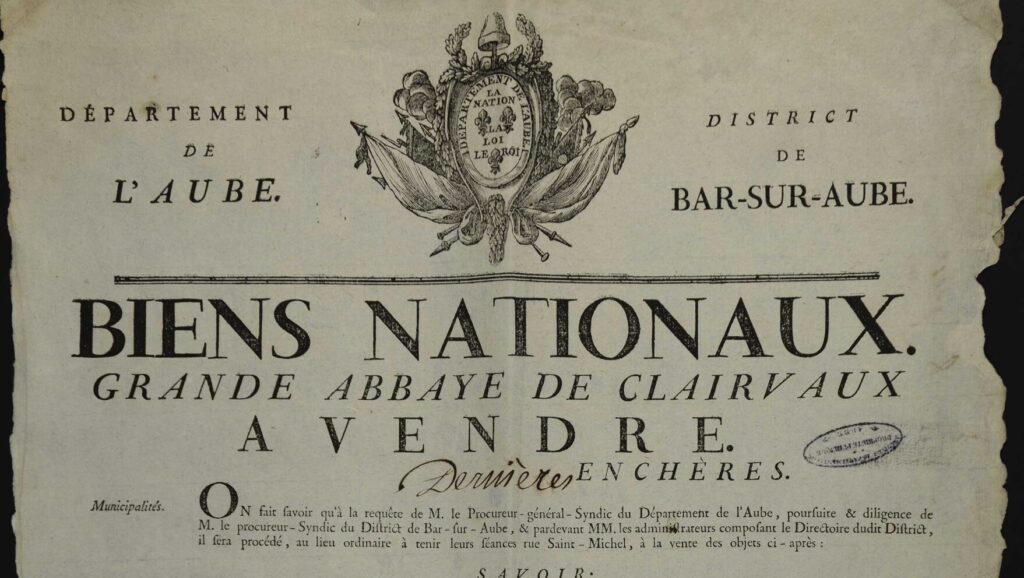

Unfortunately for the monks and lay brothers, enjoyment of their new buildings was short-lived due to the onset of the French Revolution, leading the land and its contents to be confiscated by the state and sold to an industrialist entrepreneur under the guise of a national asset in 1792.

Thereafter, the domain lay abandoned and in disuse, but in 1808 Napoleon purchased it, turning it into the largest French prison at the time. As you may have guessed, the prison is still in use today. It has been closing little by little and will close completely by 2023, ending another chapter of the abbey’s sordid history.

Main entry to the prison in 1931

Overview of the prison, 1931

The Tour: “If You Thought This Was Going to Be A Typical Visit, It’s Not”

*Spoilers ahead*

Upon our approach, the first traces of the abbey’s location were the “mur d’enceinte” (perimeter wall), followed by a massive stone gateway that leads into the complex. At this point, I could not distinguish between the prison buildings and those for abbey visitors, nor I did feel uncomfortable; it felt like any normal visit to a historic site.

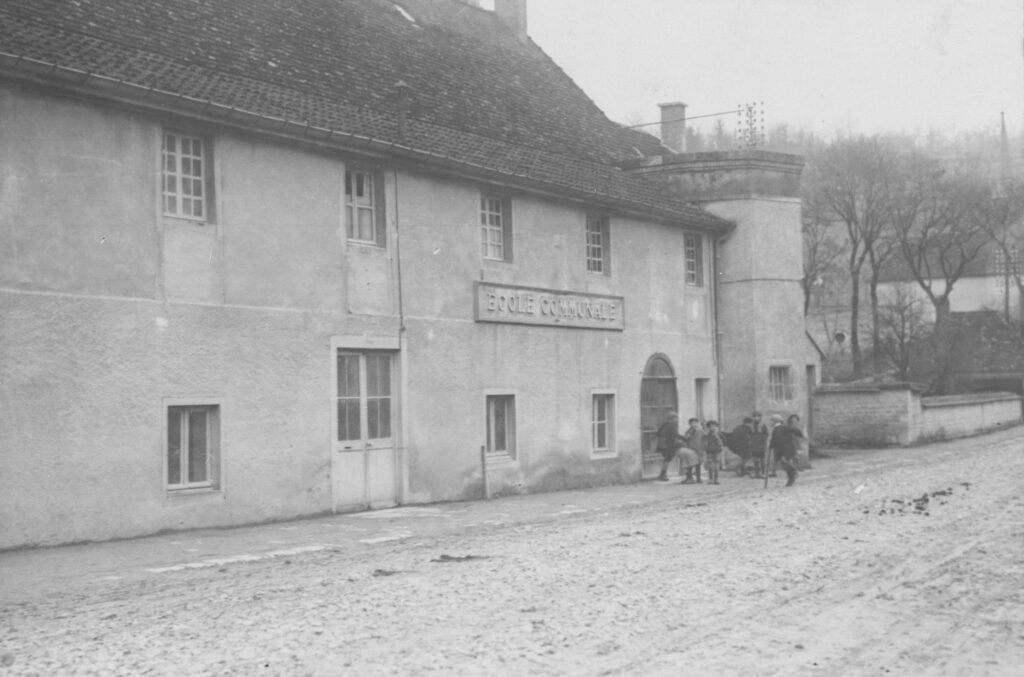

With its covered walkway and “pan de bois” (timber framed) construction, the “Hostellerie des Dames” immediately drew my attention. Built in the 16th century, it was intended to house the (female) spouses of visitors to the abbey, but was later turned into a tavern to commercialize the monks’ wine, then a primary school in the 19th century and now houses the reception and exhibition area.

Entry to the Public School, 1931

The Hostellerie des Dames, 2020

The visit begins here with an informational video that plays while you wait, followed by the official beginning of the tour taking place in the chapel of the children’s prison (constructed 1860), visitors are given an overview of the history of the abbey and the importance of Bernard of Clairvaux. Our tour guide did a great job at explaining this, answering questions, and speaking clearly and slowly for those who were not native French speakers (several people in the group were from the Netherlands).

Despite the impact that Bernard of Clairvaux had on the spread of the Order of Cistercians, and the importance of the Abbey itself, the sole vestige of the 12th century is the lay brothers’ building, which has been tediously restored to its original state following its use as the women’s prison.

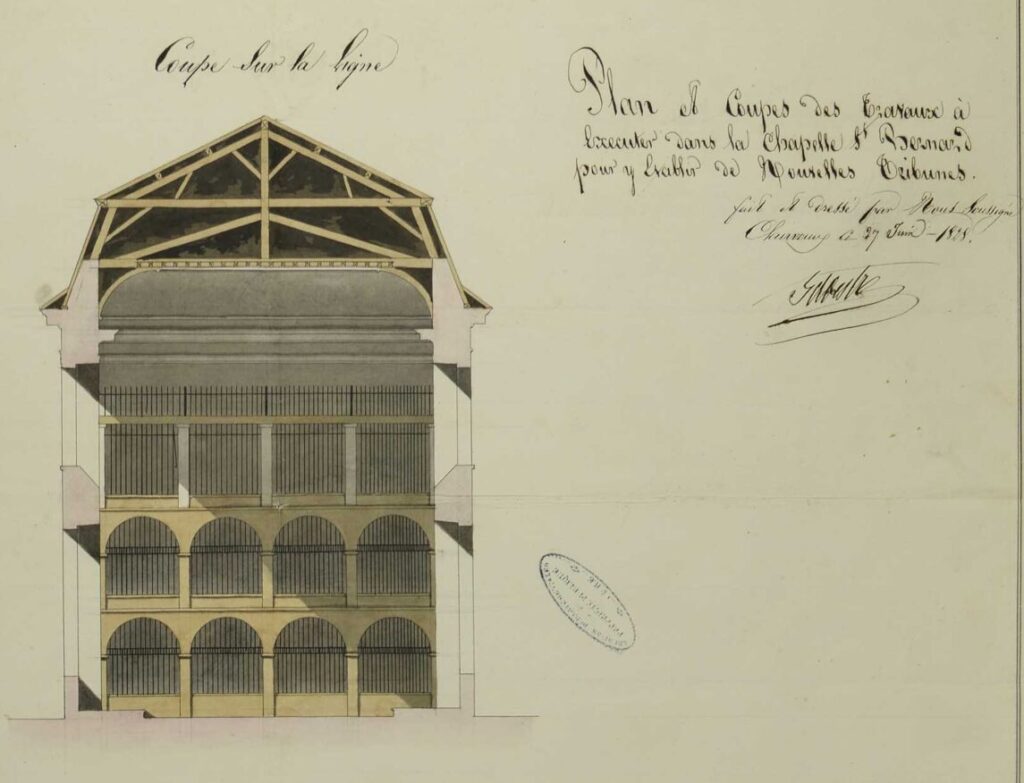

Although the traces of the women’s’ prison have all but been effaced in the lay brothers’ building, the “great cloister”-turned-prison retains every inch of its turbulent history. Used as the principal prison building, it received its first inmates in 1813. During this period, the building was augmented, and a mezzanine added to allow for the detention of 1500 prisoners at once. In this mezzanine, cells sleeping 20 men became the perfect place for nefarious activities since the guards dare not enter for fear of being jumped. Their sole means of regulating the prisoners was by three or so peep holes in the walls and door, but these still had blind spots.

In 1875, one of the new Constitutional Laws made cellular confinement compulsory, therefore, the prison administration installed what are known colloquially as “cages à poules” (chicken coops), allowing for better surveillance of the prisoners while protecting guards from harm. These were unheated 1.5 x 2-meter (5 x 6.5 ft) cells used up until 1971, the end of construction of the modern prison buildings.

Nothing prepared me for these “cages à poules,” and it was not until we had finished our tour of the room that our guide told us how long they had been in use. I think at that moment, we fell far more silent than we had already been. The atmosphere was not just oppressive, but the nature of the building’s abandonment and its “as is” state is most remarkable. For instance, one of the rooms in which the cages are installed had been partially converted into a makeshift movie theatre, complete with screen and star-clad ceiling. An initiative of the inmates, this theatre once again is an inadvertent yet touching reminder of the humanity of the persons incarcerated there.

I have intentionally decided not to include photographs of these cages à poules because they are truly something that must be experienced firsthand. A photograph could never do the pure emotion of it justice.

Writing about this right now, I am getting quite emotional.

I recall our exit from the lay brothers’ dormitory/the women’s’ prison and the beginning of our “incarceration,” complete with the locking of the exterior gate behind us (for our safety of course) as we entered an area enclosed by a barbwire-topped wall probably three times my height. As we walked towards the 18th century cloister, there was no way of knowing that such a beautiful façade hid such a dark secret, but upon entry to the interior of the cloister, it started to really sink in. I could not help but think about the intended use of the open arcaded gallery, meant as a peaceful space where the monks could circulate and contemplate, completely enclosed by bars, windows and concrete.

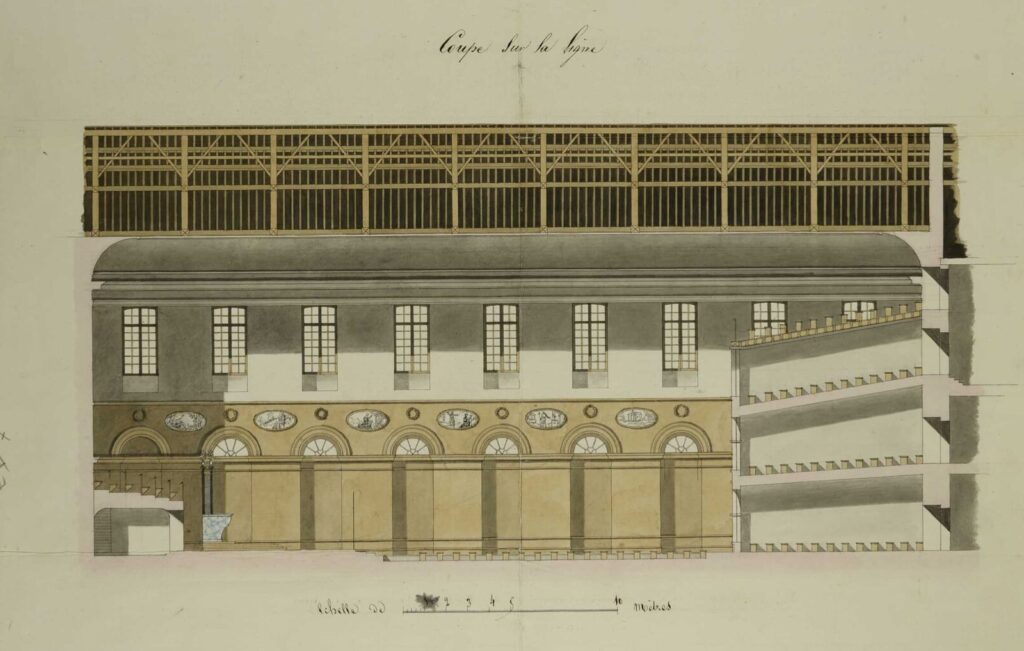

The last part of the cloister that we visited was the refectory-turned-chapel. Completed in 1774, this area is extremely sumptuous in decoration and almost incongruous with the Cistercian’s beliefs. In times of the prison, the refectory was turned into a chapel to provide the prisoners a place of worship since the medieval abbey church had been demolished. Conservation and restoration of this part of the building has given it back some of its previous splendor, all the while conserving traces of the chapel conversion.

Why Should You Visit?

Although you will not be visiting much of an abbey, I highly recommend making a visit to Clairvaux nonetheless.

Not only was the abbey itself an important part of French history, but its transformation and adaptation into a prison is a lasting reminder of a less glorified side of the French Revolution and its impact on religious communities as well as their domains. It is a rare glimpse into the past, guaranteed to render you speechless, if only for a moment.

Inmate in the shower room, 1931

Inmates in the woodworking atelier, 1931

It is clear that the abbey still requires a lot of conservation and restoration work, but the work already completed does well to take into consideration all facets of the buildings’ use.

At present, several conservation programs are underway, with plans to conserve and open the modern prison to the public following its closure in 2023. I am really excited for this and I will definitely be first in line!

If you cannot visit in person, here is an interesting video (in French, without translations- sorry) that gives a good overview of the buildings.

To learn more about the abbey’s role as a prison, how monks invented the prison sentence and how monasteries served as models for institutions of punitive confinement, take a look at this interactive and well-researched webdocumentary (again in French, sorry!).

How English Friendly is it?

Unfortunately, the visit to the abbey is not at all English-friendly, nor is their website. Tours are given in French and Dutch only, so you will need some proficiency in vocabulary concerning architecture, religion and incarceration if you want to follow along.

However, in my opinion, you don’t really need to speak French to go; the architecture will speak for itself. You may not understand the tour, but honestly mostly everything they will tell you, I have already mentioned above. Go for the experience instead.

Tips and Other Information

The only time you may feel a bit weirded out is when they request your ID. This definitely makes some visitors feel uncomfortable, but they are legally obligated to do this because the prison is right next door. Fear not, they lock the cabinet as well as the building whenever it is unattended; you will get the ID back after the tour is finished—just don’t forget to pick it up!

Also don’t bring your camera or anything, ‘cause phones and photos are prohibited (for now)!

The tour will last about 90-120 minutes depending on the group size and the guide, so plan that into your schedule.

The abbey hosts what they call the “Marché Monastique” several times a year where they sell products from abbeys throughout France and the world, check their site for details.

All other information can be found on their website.

If you are interested in seeing or visiting some other Cistercian cultural heritage, take a look at this website for some inspiration!

If you would like to visit an abbey where most of its buildings are intact and its carceral history has been erased, I suggest taking a look at the Abbey of Fontevraud in the Loire Valley.

Enjoy your visit!

Bisous,

Rose

Read More:

Rose

Thank you for this article. I visited thre in 1966 or sp but did not feel welcome. Was a rpison there at that time/

Bill Reed

Knoxville Teeessee USA

w2reed@yahoo.com

Dear Bill,

Thank you for your comment. I am happy that you found my article and glad to know you enjoyed it.

I am sure a lot has changed since 1966, and you could probably see that yourself while reading.

There is still a prison on the other side as I said, but that will also be turned into part of the tour when it is fully closed in 2023.

I hope you will consider giving it another visit if you come to France after then. It is likely to be much more welcoming as they depend greatly on tourism to remain open. Although I have to say I am disappointed tours are not given in English as I think that would be beneficial to them, but who knows what the future may hold?

Kind regards,

Rose